Longform

Human Trafficking on I-44

It’s no secret that human trafficking—a shadowy and complex crime that’s particularly hard to track and prosecute—exists in Missouri. 417-land's location along I-44 puts us among the local hot spots where sex trafficking has cropped up and grown recently.

By Stephanie Towne Benoit

Jan 2018

Deep in the woods, Lyla, a young woman raised in 417-land, realized that this was the chance she’d prayed for. Clasping a pair of old gloves containing her possessions, she made a break for it, her feet burning with pain from the boots that rubbed against her bare skin.

Disoriented and frightened, she reached a country highway, where an oncoming car caught her eye. She scrambled off the road, fearing that the vehicle transported the man who had abducted her during a drug deal. She remembers being flung on the back of a dirt bike or sandwiched in a car between guns and air pressure machines as she was transported from house to house and forced to cook meals, prepare drug paraphernalia and clean the filthy locations where she was kept. “Life was beyond horrific at that time,” she says, recalling being inflicted with unremitting physical, sexual and emotional abuse for months on end. Practically every aspect of her life was controlled. Kept utterly isolated, she was forced to conceal the truth of her circumstances from her family, with whom she could communicate only on sporadic, supervised phone calls.

She’d tried escaping before, but never successfully. Once, after being abandoned in a rural area, she escaped to the safety of a family member’s home, where she was tracked down and abducted once more. On other occasions, her captor would abandon her in the wilderness without food or water for days at a time. She remembers screaming into the darkness for help, only to be picked up again and moved to the next location. “It was like there was no escape from it,” she says.

Lyla was wearing these hiking boots when she ran out of the woods to escape her captor.

Lyla’s experiences echo those of innumerable men, women and children across the globe ensnared by human trafficking, a form of modern-day slavery involving the use of force, fraud or coercion to obtain labor or commercial sex. (Lyla’s name was changed to protect her identity.)

The exact scope of the problem isn’t clear due to myriad complicating factors. For example, the crime is easily confused with prostitution, and traffickers may be prosecuted using different statues or for other crimes entirely, thus obscuring any reliable statistics. But murky as the issue is, local experts agree: human trafficking exists in 417-land.

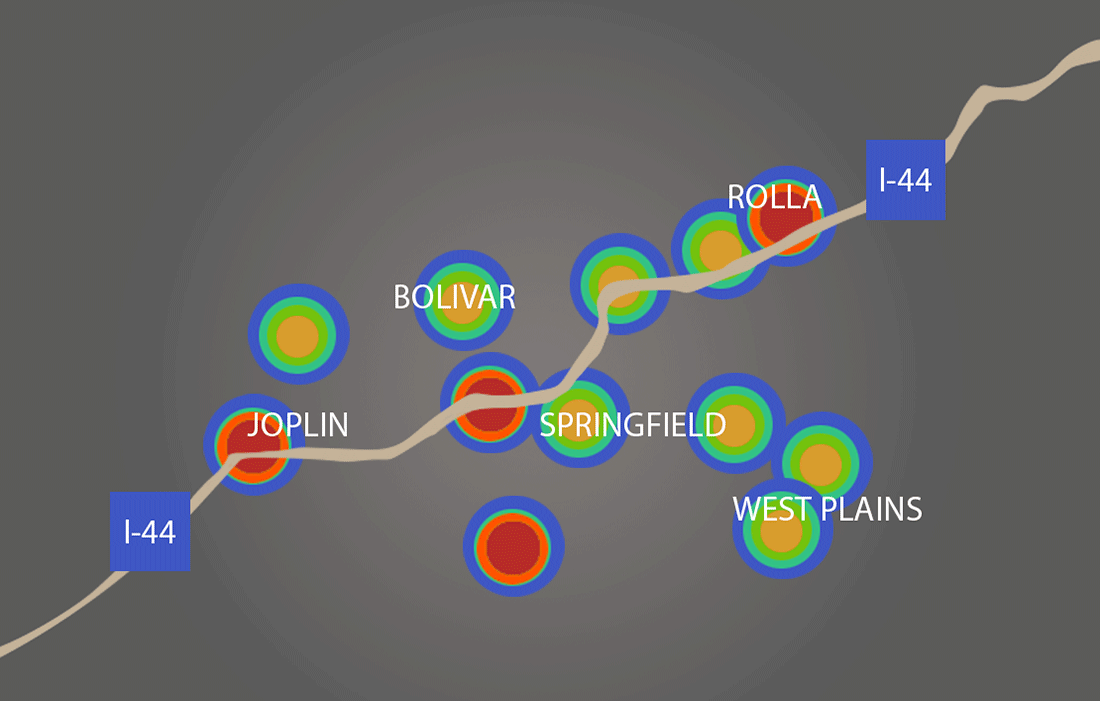

Many credit the crime’s local presence to a key element: the major interstates allowing traffickers to flow in and out of the area. That’s supported by the National Human Trafficking Hotline’s Missouri call data tracking where requests for help and possible reports of the crime originate. Outside of Kansas City and St. Louis, the state’s most concentrated hot spots are close to home: Joplin, Springfield and other locations along the I-44 corridor.

How It Starts

In addition to the existence of major arteries like I-44, there are numerous other factors that play a role in allowing traffickers to trap and control victims for commercial sex or forced labor in 417-land. Jen Osgood, educational outreach instructor of Joplin-based human trafficking nonprofit Rapha House, says it’s common for the drug trade, a prevalent local problem, to become enmeshed with trafficking. She saw that entanglement firsthand when her mother fostered a teen whose parent had prostituted her in exchange for drugs.

Drugs were a hugely significant piece in the puzzle of factors that made Lyla vulnerable to trafficking. As a young adult, her life was in a tailspin. Her relationship with her boyfriend, with whom she had a baby, was falling apart and eventually became abusive. He disappeared from her life and took their child with him, leaving her desperate and lonely. Eventually, she started drinking and, after some time, tried methamphetamine.

Not long afterward, she found herself craving more meth. So, joined by a close family member who was also using drugs, she sought out someone who could provide it. That pursuit eventually led them to the man who became her trafficker and ripped her from the life she knew after abducting her during a drug deal.

Trafficking can begin as simply as an individual, perhaps from another country, coming to the region to work to pay off a debt of some kind, says Joplin Police Detective Chip Root. However, the trafficker might charge that person room and board, perhaps restrict their movements, control their legal documents, force them stay on the premises, or threaten to harm their families if they don’t cooperate. “If that’s not slavery, I don’t know what is,” Root says.

Take for example a multi-agency investigation in which search warrants were served at more than a dozen Greene County spas, massage parlors and residences due to suspected human trafficking and prostitution activity. It’s believed that some of the young women working at the businesses, who were largely immigrants from Asian countries, were being held against their will and made to perform sexual acts on customers. Greene County Prosecuting Attorney Dan Patterson confirmed that the women were Asian but could not comment on their status or if they were being held against their will, due the ongoing nature of the case. This Missouri investigation was part of a broader multi-state investigation.

People can also become victims through calculated enticement says Savannah Stepp, director of NightLight Missouri, the local branch of NightLight International, which works with victims of sex trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation. For example, a trafficker might pursue a young victim romantically and use that intimacy to coerce individuals into commercial sex—and trap them there. “They believe that person loves them, and it’s a relationship,” Stepp says. “It may not be a healthy relationship by any means, but it’s a relationship.”

Called a Romeo pimp, such a person preys on the basic desire for attention and connection. Shannon Tatum, who works with Springfield-based I Pour Life, says that makes the at-risk youth she assists—many of whom have experienced neglect or abuse, family instability or poverty—vulnerable. “They want to be wanted,” she says. “They want to feel attached and love and that sense of family.” She recalls coaching a trafficked teen who was progressing in I Pour Life’s program only to be trapped once more. “So often it’s not a choice because sometimes these girls are kidnapped and held captive, but even when they are not, their minds and their hearts are held captive,” Tatum says.

Missouri by the Numbers

Operated by Polaris, a Washington, D.C.–based anti-human trafficking organization, the National Human Trafficking Hotline received 34,068 total human trafficking–related calls, emails and online tips in 2016. Much of that communication came from Missouri, which had the 17th highest call volume in the nation. Based on the hotline’s 2016 data report for Missouri, here’s how those tips break down.

Total hotline communication from Missouri

426

total hotline phone calls

135

unique cases of potential human trafficking in Missouri reported to the hotline

18.5

percent of those were potential labor trafficking

70.4

percent of those were potential sex trafficking

38.5

percent of suspected sex trafficking victims were minors

71.1

percent of suspected sex trafficking victims were female

Stopping Traffickers

With so many complicated factors, law enforcement agencies across the region remain vigilant for the crime, including Springfield Police Chief Paul F. Williams. “People need to realize it does happen in the United States,” Williams says. “It’s not just an international problem, and our young people are not at risk only when they are overseas.”

He points to a recent Springfield case involving a local man who was charged with two counts of sexual trafficking in the second degree, two counts of endangering the welfare of a child and one count of statutory rape in the second degree. The two victims were rescued after contacting one of their friends for help, who told the police what she’d learned. The outcome of that case will be decided when it heads to circuit court later this year.

Due to insufficient manpower, such cases come to the department’s attention through tips, not proactive investigating. But Williams hopes that will change, citing the department’s goal of starting a vice unit to investigate vice activity, including trafficking, by 2019. “We have never had one, which would allow us to proactively go after and investigate not just on a complaint basis, but seeking out some of these things, from street-level prostitution up to coordinated, organized sex trafficking on a wide scale,” he says.

It’s not unprecedented for such rings to appear in 417-land, so that watchfulness is warranted. For example, federal prosecutors convicted members of a multinational criminal enterprise involving the forced labor trafficking of foreign workers, many of whom were recruited under false pretenses, placed in service and hospitality jobs in locations around the country—including some Branson hotels—and controlled through manipulation and threats.

The Branson Police Department says it hasn’t yet encountered and charged its own trafficking cases but acknowledges that a severe lack of staff and resources may limit their efforts. “That’s what keeps me awake at night: what we don’t know is occurring in our community,” says Chief of Police Stanley Dobbins. He hopes that the Branson sales tax that was voted through in November will lead to more public safety funds, allowing increased capacity for the department to investigate all criminal activity, including trafficking.

In the meantime, Branson Police Sergeant Sean Barnwell says the department remains vigilant for traffickers. For example, investigators are trained in recognizing trafficking, and the force recently added two new officers to monitor activity at hotels and motels, locations where victims can work or be harbored. “I think that that, as far as human trafficking, gives us a leg up on knowing what’s going on out there at those locations,” Barnwell says.

Much of Joplin detective Chip Root’s investigative efforts center on thwarting illicit online activity. He serves as task force commander of the Southwest Missouri Cyber Crimes Task Force, which covers 22 regional counties and focuses on cybercrime’s intersection with crimes against children and child sexual exploitation, which can easily evolve into trafficking. For example, criminals can coerce a child into creating pornography that’s then trafficked online, which Root believes can fall under the definition of human trafficking. Or, criminals might utilize the internet to arrange meetings between buyers and victims at locations like casinos before vanishing and resurfacing elsewhere.

Such highly transient situations are challenging for local police to pin down, but Root says that’s where the task force comes in. Many of its members possess federal commissions with the FBI, Homeland Security or U.S. Marshals, allowing them to investigate and charge cases beyond their jurisdictions and effectively collaborate with those agencies. “That’s the beauty of it,” he says.

Bringing Justice

Once investigated, trafficking is often prosecuted federally. In 417-land, that’s done by the U.S. Attorney’s Office in the Western District of Missouri. Encompassing locations in and around Kansas City, St. Joseph, Columbia, Jefferson City, Springfield and Joplin, the district has long been at the leading edge of human trafficking prosecutions with its Human Trafficking Rescue Project, a federal task force launched in 2006.

Concrete numbers are hard to come by due to factors such as accused traffickers pleading guilty to other charges, but at one point, the Western District of Missouri had prosecuted more trafficking cases than any other district in the United States. That includes a groundbreaking case—centered on the torture and sex trafficking of a woman in Lebanon, Missouri—that utilized the Trafficking Victims Protection Act in the conviction of Johns, marking the first time nationwide that buyers had been convicted under the statute in a case involving an adult victim. It was also the first time that buyers were prosecuted in a case involving a victim rather than in an undercover sting.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Teresa Moore, who leads the task force and handled the case when it went on appeal, says that targeting the demand side of human trafficking is crucial. “I think that prosecuting pimps is certainly really important, but they are not operating in a vacuum,” she says. “The demand side is what really drives the cases and drives the incidents.”

Prosecutors are also on the move at the state level. Last year, Missouri Attorney General Josh Hawley announced a range of initiatives such as forming a new trafficking-focused unit in his office. That unit assisted in the effort to investigate the group of Springfield-area spas and massage parlors suspected of being involved with human trafficking.

Hawley has also issued new consumer protection rules to target such businesses that serve as a cover for trafficking. A first-of-its-kind approach in the country, the latter move is significant because trafficking convictions have relied on victim cooperation, which can be challenging to ensure given the harrowing circumstances they’ve experienced. “We think this is a bold and innovative new approach that will give us another tool to go after traffickers,” Hawley says.

Those rules are also a linchpin in the investigation his office has launched into backpage.com, the website through which trafficking transactions have been known to occur. “It’s vital to shut down the supply that is being generated over the internet and also to shut down the predators who are using the internet to target those who are vulnerable,” he says.

Hope and Healing

Alice Weimer, a licensed professional counselor who chairs Springfield’s Stand Against Trafficking Coalition, believes that protecting those vulnerable populations hinges on community awareness.

To nurture that awareness, Weimer presents in schools and community groups about recognizing and reporting trafficking. She says it’s not uncommon to see 417-landers realize that the warning signs she highlights—for example, unexplained gifts or frequent absenteeism and travel—are present in the lives of people they know. “It dawns on them as I’m talking,” she says. “They start to say ‘Hey, what should I do about this?’ You want to get help for her. And you may be the only people in a position to do that.”

Groups like Stand Against Trafficking Coalition also provide training to area law enforcement. “There are some very specific signs of human trafficking that are very easy for people to miss, including law enforcement,” says Joplin detective Chip Root. Knowing those indicators is vital because victims may be afraid to come forward, whether because they fear being perceived as complicit, distrust law enforcement, dread being returned to their home countries, and so on. Missouri State Highway Patrol Sergeant Danielle Heil says she’s seen such barriers impede law enforcement when they encounter suspected trafficking victims. “I would say that’s probably our number one stumbling block right now: finding a way to get them to trust us and divulge that information to us,” Heil says.

Although trafficked persons are often kept isolated, as many as 87 percent of the survivors participating in recent research reported having contact with a health care provider while they were trafficked. “We have the opportunity to access a huge population of human trafficking victims,” says Dawn Day, sexual assault nurse examiner at Mercy Hospital Springfield. To take advantage of that proximity, Day says that more health care professionals—especially those in emergency rooms or urgent care, which tend to see more trafficking victims—must be trained to look for the crime. But rescuing victims, who are sometimes taught to distrust authority figures, also requires fostering an atmosphere in which survivors feel comfortable seeking assistance, says David Barbe, M.D., a physician at Mercy’s Mountain Grove family medicine clinic and president of the American Medical Association. “If there is a continuous culture of that in the health care environment, we will get more individuals who are being trafficked to confide and open up and seek the help that they need,” he says.

Heil says another hurdle is securing assistance for victims. Rapha House’s Jen Osgood, whose organization is part of the Southwest Missouri Anti-Human Trafficking Coalition, says that’s essential because victims may need the most basic of necessities when they are rescued. “They are not going to have anything, if they are a trafficking victim, except for what they are wearing,” she says.

To meet victims’ needs when law enforcement recovers them in and around Joplin, the southwest Missouri coalition provides clothing, snacks, water bottles and hygiene items in Go Bags. Those provisions may seem trivial, but Root says their impact is significant. “The first thing we do is we have to give these women some dignity back,” he says.

Survivors’ next steps toward healing can be exceedingly complex and require navigating wide-ranging needs and trauma. NightLight Missouri, which has coordinated onetime or ongoing assistance for victims of trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation through its Restoration program since July 2015, says coupling that concrete aid with compassion can have a powerful effect. “In working with survivors, sometimes all we are really providing a woman is a stable, healthy, loving relationship,” says Shauna Storey, chief operations officer of NightLight International. “It’s amazing how far they can get on their journey with just that.”

Out of the Shadows

Lyla watched the car drive past. A few minutes later, it was heading back her way, sending fear coursing through her. But rather than facing her trafficker, she encountered a local couple. They approached her and asked if she was alright, which she hadn’t been asked in more than a year. She remembers coming into gas stations on rare occasions during her captivity, only to be ignored by anyone she encountered. “I don’t know that I wouldn’t have just dropped down to my knees and wept because someone just cared enough to even ask me if I was okay,” she says.

The couple called Steve and Tressa Dunlap, founders of On Time Ministry, a 417-land organization that cares for trafficking victims, former prostitutes and women at risk of exploitation. Operating homes in Mexico and 417-land, the group also arranges services for those women, such as medical treatment and counseling. The organization took Lyla in, giving her safety and the support to recover.

The Dunlaps say they’ve sheltered dozens of women in Southwest Missouri, many from within 100 miles of the home, but are often unable to accept referrals because demand is such that the home is continuously occupied. To meet that demand, the Dunlaps are in the process of opening another home in a nearby town. “We are not trying to grow a ministry,” Steve says. “We are just trying to help girls.”

More individuals—specifically sex trafficking survivors who are minors—will be assisted at a new 417-land shelter that’s spearheaded by partners including F.R.E.E. International, which works on human trafficking initiatives around the country.

Although Lyla has more healing to do, she’s made considerable progress. She has launched a budding small business that she’s excited to grow in the future. Being in a place of recovery has allowed another passion to develop: to make a difference by assisting victims of human trafficking and exploitation. “I am ready to take on anything, and I am ready to do anything to help any girl get out of that situation,” Lyla says. She currently serves that mission by helping out the staff of On Time Ministry. “My ultimate goal in life is definitely to spread hope to people that have none,” she says.