Lifestyle

5 Best Museums in Springfield, Missouri

Take in something new this winter by learning about the culture and history of the Ozarks at these local museums.

By Michelle Lewis

Jan 2023

1. Springfield Art Museum

1111 E. Brookside Drive, Springfield; 417-837-5700

Must-See Exhibit This Month: Humanities, Vol. 2

The Springfield Art Museum has a permanent collection featuring works from artists around the world. Rotating and traveling exhibitions are always moving in and out of the museum, which means there’s always something new to view when you visit.

2. History Museum on the Square

154 Park Central Square, Springfield; 417-831-1976

Must-See Exhibit This Month: Wild Bill Hickok & The American West

Take a journey through time at the History Museum on the Square. See the story of Springfield unfold as you walk through galleries featuring the history of the land and the people who made the city what it is today.

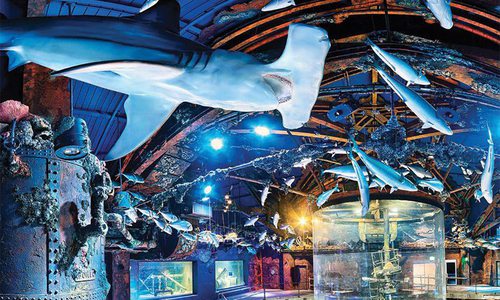

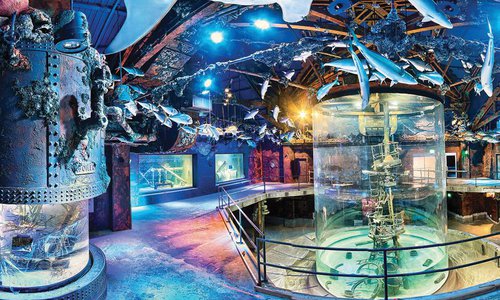

3. Wonders of Wildlife National Museum & Aquarium

500 W. Sunshine St., Springfield; 888-222-6060

Must-See Exhibit This Month: Nature’s Best Photography Exhibit

Travel around the world and immerse yourself in the beauty of nature during any season at Wonders of Wildlife National Museum & Aquarium. Walk through exhibits and galleries full of elaborate diorama-style wildlife habitats and see live creatures on display from the world’s oceans and rivers. And don’t miss a chance to feed the stingrays while you’re there.

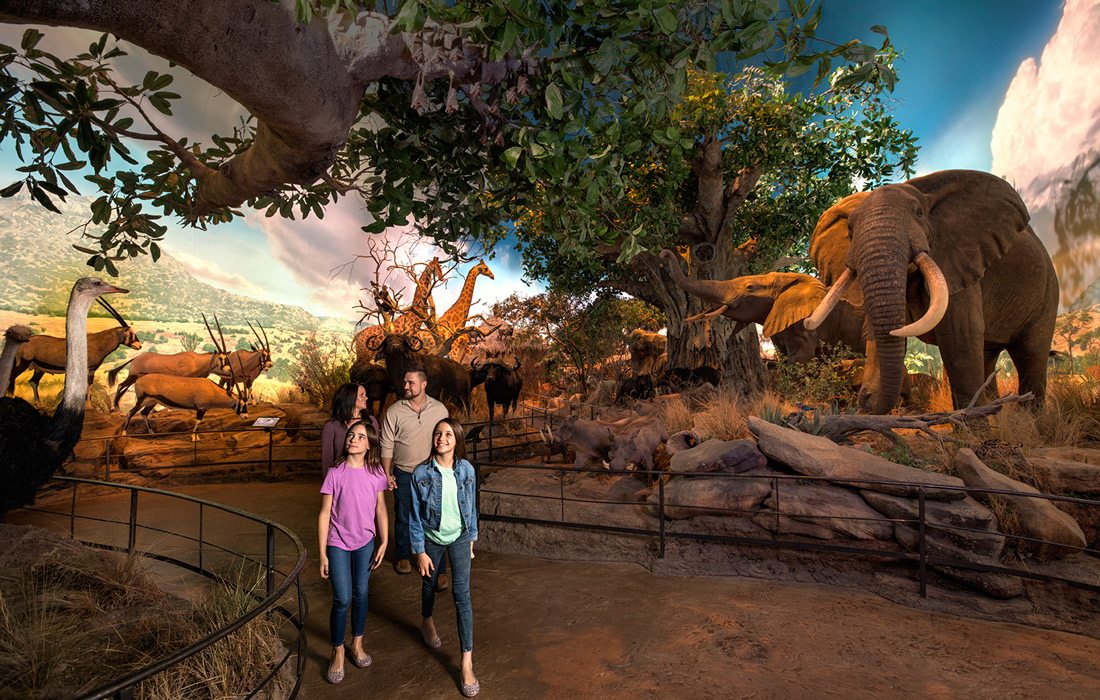

4. Ancient Ozarks Natural History Museum

150 Top of the Rock Road, Ridgedale; 417-339-5306

Must-See Exhibit This Month: George Washington’s hair preserved within a locket

See the huge mastodon and short-toothed bear skeletons to see some of the creatures that used to roam these lands. And through the numerous halls of Native American artifacts, you can get to know the tribes who lived throughout Missouri.

5. Missouri Institute of Natural Science

2327 W. Farm Road 190, Springfield; 417-883-0594

Must-See Exhibit This Month: The Triceratops

Discover prehistoric wonders when you visit the Missouri Institute of Natural Science. Constructed after the accidental discovery of a perfectly preserved cave from the ice age, this museum holds hundreds of artifacts and specimens. Although the cave is closed to the public, the institute’s grounds hold an area that allows visitors to experience searching for fossils firsthand.