Lifestyle

Five Questions with Suzanne Walker-Pacheco

After Air Force bases, floating houses and rainforests, Suzanne Walker-Pacheco settled in 417-land to raise her son and serve as a physical and biological anthropologist.

Written by Juliana Goodwin | Photos by Brandon Alms

Nov 2016

Suzanne Walker-Pacheco, Ph.D., is a physical and biological anthropologist and professor in the department of Sociology and Anthropology at Missouri State University. As an Air Force brat, she lived in Guam as a child, and every time a

National Geographic special came on that involved primates, her dad would yell and she’d come running. During her first semester at San Diego State University, she took an anthropology class, fell in love with the subject and made a career out of it. Field studies have taken her from Sierra Leone to the Amazon to study primates. While working in Venezuela she met her husband, Enrique Pacheco, and they moved to California. He was diagnosed with lung cancer and died at age 40 before the birth of their only child. Shortly after, Walker-Pacheco relocated to Springfield for her job and has raised her son as a single mom. Outside of work, she loves to hang out with her teenager and watch movies, ride her bike and play racquetball.

417 Magazine: As a biological anthropologist, you sometimes identify human skeletal remains for law enforcement. How does that work?

Suzanne Walker-Pacheco: We are very familiar with the human skeleton and anatomy. I have worked on a number of forensic cases starting with California. I have done quite a bit of it here as well, mostly [in] Camden County. I have helped narrow down identification to age, sex and ancestry, and then [the police] can refine their searches based on that information.

417: Where is the most fascinating place you’ve done fieldwork?

Walker-Pacheco: When I started my dissertation I went to Brazil 400 miles west of Manaus. It was very remote. I went by myself. I lived on a floating house and hired someone who had worked with a well-known researcher. When I would go out at night, I’d see glowing eyes of the caiman. They would be lined up on the supports of the floating house. I spent some time at the mouth of a river watching different groups of rare monkeys, Uakari, who are bald on top of their heads. I lived with people in stilt houses and helped them plant watermelon seeds, went through the process of turning yucca into flour, cleaning fish, learning Portuguese. That was the most amazing and rewarding experience.

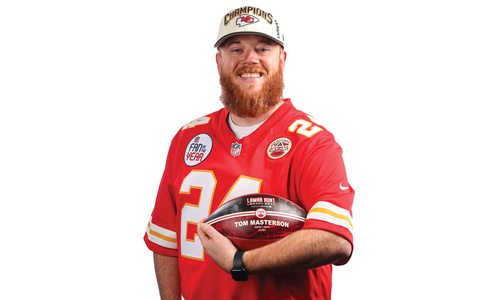

Who doesn’t love an anthropologist with a sense of humor? Suzanne Walker-Pacheco donned a primate mask for her photo shoot.

417: Have you had a “discovery” in your career?

Walker-Pacheco: In Venezuela, I was the first one to do a long-term study of the white-faced saki monkey. They were known as being very shy, and when anyone tried to study them, they would leap away. When my professor established this site [for the field study], it was on an island. We were able to get them used to our presence. I was the first to complete a study on a cryptic primate and got a lot of good data.

417: What do you study in Springfield?

Walker-Pacheco: Health issues in the Latino community in Southwest Missouri have been my main focus. The first study was in Barry, Newton and McDonald counties. We had 300 heads of household answer this 10-page survey. I was interested in cultural perceptions of illness, access to medical care, barriers to medical care. We got good feedback. Then I started working with a dietetic professor, [who was] someone from the physician assistant program, and did a year-and-a-half diabetes prevention program with Latino kids in Springfield: “Por La Salud de Nuestros Niños.” Diabetes rates are so high in Latino populations, especially immigrants. Diabetes hits Latino kids younger and younger. We studied 64 Latino children ages 3 to 9. There was a weekly interactive health education program, nutrition and exercise education, information for caregivers and daily nutritional intake and physical activity that was chronicled by their caregivers. The families told us they became more aware of what their children ate by charting it. So they starting balancing their kids’ diets. They started eating healthier as a family, and that was unintended and a very nice consequence. I also went to Mexico to collect comparative data on diet, activity level and physical measurements. The level of overweight kids who immigrated to the U.S. was much higher than in Mexico. Dietary quality worsened upon moving to the U.S., and activity levels were much lower. That was rewarding research.

417: What was the most rewarding aspect of your career?

Walker-Pacheco: Fieldwork and teaching. I love teaching, especially when you have students that were not doing well at first or not interested, and then with individual attention, they start excelling.