Lifestyle

War Stories of 417-land Soldiers

The days of warriors sitting around the campfire sharing battle stories might be long gone. Instead we had four local soldiers tell us their stories.

Photos by Brandon Alms | Additional photos courtesy Jeremy Whitworth, Justin Hall, Carl Phillips & Nick Ibarra

Nov 2016

Sometimes an idea strikes such a deep chord, it can’t be ignored. After reading Sebastian Junger’s book, Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging, we were inspired to share the stories of a few local veterans.

In his book, Junger explains that despite a decrease in the number of soldiers who see combat, the number of soldiers suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder is at an all-time high. Junger hypothesizes that the cause of PTSD lies not in the trauma experienced by the soldiers while at war, but in the culture to which the soldiers return. A culture that is increasingly alienating. A culture that sends the unspoken message to our soldiers that we don’t want to hear about their experiences. In other words, “Maybe the problem isn’t them, the vets,” he says. “Maybe the problem is us.”

The days of warriors sitting around the campfire sharing battle stories might be long gone, but with Veterans Day coming up on November 11, we put the words of four local soldiers on paper and are sharing them on the following pages. Read on to hear about what it’s like to serve overseas from individuals who have done it themselves.—Vivian Wheeler

The Bridge to Baghdad

Jeremy Whitworth served as an active duty Marine from 2002 until 2006 and as an active reservist from 2006 until 2010. A member of the 3rd Battalion, 4th Marines, Whitworth was part of the military’s successful effort to take Baghdad during the Iraq War in early April 2003. Here he recounts his story of when Baghdad fell, starting with his squad’s effort to cross the Diyala bridge, nine miles from the city’s downtown.

By Jeremy Whitworth as told to Vivian Wheeler

When we came up to the bridge crossing the Euphrates, enemy troops had blown out two big sections in the bridge. We immediately had to dismount our amphibious assault vehicles (AAV) because of the holes in the bridge. Combat engineers then brought out these floatable bridges. They looked like grated steel. It was flimsy, like sheet metal. We were taking fire from across the bridge and getting hit with mortars—60- and 80-millimeter mortars are getting shot at us.

These combat engineers who had laid down these bridges, the whole time they were showing so much courage because they are out there by themselves working. They got those two minibridges down, and they start just yelling, “Come on. Let’s go, let’s go.” Everybody gets up from their concealment—or from whatever cover they had—and we start hauling ass. We run across the steel, and it’s flexing, and there’s a 30-foot drop-off into the Euphrates below us. There are a few bodies scattered across that bridge, we took a few guys out coming up to the bridge there. Those faces will never leave my memory.

The fire got real heavy when we started coming across. I remember it pinging off the bridge everywhere. It was crazy. We fought our way across the bridge, and then we got on line.

1. A statue of Saddam Hussein falls in Firdos Square, Baghdad. 2. Jeremy Whitworth and his squad members prepare to invade Baghdad while waiting at Camp Ripper in Kuwait. 3. Jeremy Whitworth sits on top of a building in the city of Baghdad in 2003.

We started firing and moving. I would say “moving” and the guy behind me would say “move.” Then I would get up and sprint as far as I could during the amount of time it took me to say, “I’m up. He sees me. I’m down,” in my head. Then I’d go back down and start firing. I was hitting flat with the ground because those rounds were hitting a foot above our head. When a round comes by your face, it sounds like those little firework snappers going off.

Our sergeant major was across there with us. It was odd. That’s huge leadership when your battalion commander or sergeant major comes into battle with you. The sergeant major is walking behind us, and I remembered he said, “Steady fire, well-aimed shots, keep your bearing.”

There were mortar rounds going everywhere, and hell is breaking loose. We just start getting up and firing and moving as we normally would. And before you know it, we pushed through the enemy.

Once we were in Baghdad, we popped the hatches on top of the AAVs and sat up and watched just thousands of people starting to pour onto the sides of the streets. I remember pulling into the square and seeing another statue of Saddam. We always went straight for a statue. If we saw one, it was coming down. In every major city there was a dang statue of Saddam, like a godly statue of him in a gangster suit with a cigar in his mouth.

They had to pull in a D77—a tank tower—to pull down the statue. I remember one of my buddies threw his American flag up there initially and draped it across the statue. Then one of the higher-ups yelled, “Hey, take that down.” We weren’t there to invade; we were there to liberate. Another one of the guys had the older Iraqi flag—before Saddam had changed the flag—so they threw that up over the statue, and the crowd went crazy. They were all cheering “U.S.A, U.S.A.” Later they started dragging the statue through the streets, and all of these Iraqis were taking their sandals off and smacking the statue with sandals and kicking it with the bottom of their feet, which is one of the biggest signs of disrespect in their culture.

It felt like this was it, like the war was over. But I knew in the back of my head it wasn’t. I had a feeling we were going to keep pushing.

Coming Under Fire

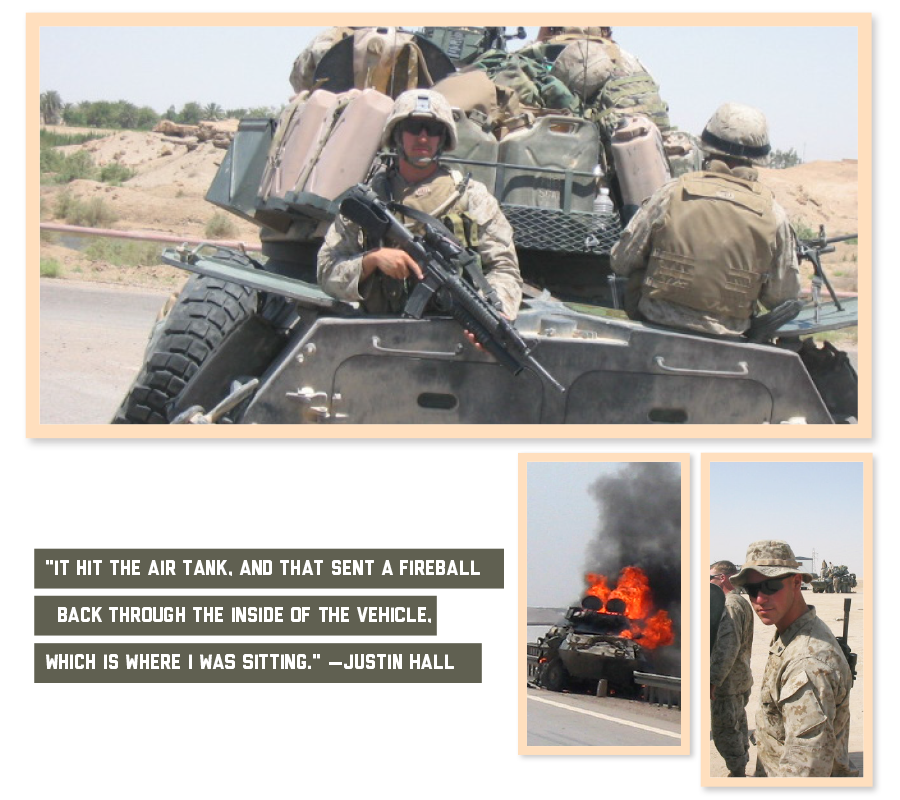

Justin Hall joined the U.S. Marine Corps in 2000. He served in active duty until 2005 and as a reservist until 2008. Read about his near-death experience after a fireball blasted through his vehicle during his 2004 deployment to Iraq.

By Justin Hall as told to Vivian Wheeler

I’ve had several improvised explosive devices go off on my vehicle. Some did nothing more than pop tires or scratch the vehicle. One of them actually caught me on fire. It was an extremely bad day. It was toward the end of our patrol, and we weren’t too far from Abu Ghraib, the now infamous prison. We were headed back to base. I was in the back of the vehicle, and I never heard it go off, but all of a sudden there was this intense heat, and then I couldn’t breathe. The vehicle was still moving, but I could tell it was slowing down and idling. I knew stuff was on fire.

We had two hatches. I was in the back, and we have what was called a scout hatch that goes out the roof and a door out the back, which was the big door that you’re supposed to go in. I tried to open that up, and it didn’t open, so then I tried to go out the scout hatch. Well, the barrel for the main gun was over the top of the scout hatch, and I couldn’t get it open. I went back to the other door and kept trying and trying. So myself, and I had another scout to the right of me—it was actually our corpsman who acts as the medic for the Marines—he was helping me push. We finally got the door open, and we fell out on the ground. I got out and my helmet was on fire. I got the rest of my scout team. They got out, they were singed as well, but no one else on the scout team was hurt. The entire top of the vehicle was in flames.

The explosion turned out to be a homemade version of napalm. It was diesel fuel mixed with other stuff, and it also had little quarter-inch by quarter-inch steel cubes that had been loaded in the IED. They shredded through the vehicle. It hit up in the front portion of the vehicle where the driver sits. It hit the air tank, and that sent a fireball back through the inside of the vehicle, which is where I was sitting. It killed the driver instantly. His name was Timothy Creiger. He was from Memphis.

So the top of the vehicle was on fire, the vehicle commander and the gunner were both hurt badly, and they actually fell off into what would be the median between the lanes of travel. They fell off of the vehicle and down on the back. I ran around and pulled the vehicle’s fire suppression system and then ran over and picked up the guys who were hurt.

The first guy didn’t look all that hurt, Jake Rhinehart. I pulled him across with some other people and took him to another vehicle. Then we went and got the gunner, Jason Simms, he was burned extremely badly. His femur was sticking through his uniform, and he was just screaming. The corpsman gave him a shot of morphine, and they went to the nearest hospital, which was the prison hospital.

And then at that point I just kind of stopped. I don’t really know why. I just started standing around kind of in a daze, like, “Okay, now that’s done.”

Then some guys came up, because all of the rounds of ammunition and everything in the vehicle start cooking off. The stuff starts exploding, and it sounds like firecrackers, but we also had some high explosives that were in there.

So as I was just standing there, one of the guys ran up and grabbed a hold of me and pulled me off to the side, and we sat there. Eventually everything did cook off.

For the Love of His Country

In 1998, Carl Phillips joined the U.S. Navy. He has seen eight deployments and has spent 18 years serving in the military. He continues today to serve as a reservist. Here he shares his experiences in and advice on different aspects of military life.

By Carl Phillips as told to Vivian Wheeler

On deploying for war for the first time

“I went to Iraq in 2003, and then my son was born on the day that I was flying out there. So I’ll never forget that day. My first son, Corbin, was born on January 30, 2003. I was in the air flying to Iraq when he was being born. I didn’t know if I was ever going to see him because I was going to war, and that was [when] the war just kicked off.”

On why he joined

“A lot of people have asked me, ‘Well, how do you feel about serving in Iraq? How did you feel about serving in Afghanistan?’ And for years, I never really had a good answer, but I do now. Do you want to fight them there, or do you want to fight them here?

I say we fight them in their backyard because my son plays in my backyard. I don’t want to have him exposed to that kind of violence. I’d much rather take the fight to the enemy instead of having the enemy build up the capability and bring the fight to us, which is what would happen if we allow them to do it. We saw that on 9/11. That’s kind of how we learned our lesson.”

On boot camp

“Imagine you’re a computer, and you’ve got all this data that you don’t necessarily need when you go to boot camp. So, they basically take this laptop that you give them—the laptop I’m paraphrasing as a person—and they just, like, wipe it. They delete the files. And how they do that is, they break you down to the simplest things.

Everything is very structured. So you get up at certain times, you eat at certain times, you walk a certain way, you talk a certain way, you do physical activities a certain time a certain way. So then they start uploading these new files and all those things I just said are what they’re uploading. So basically, they reprogram you.”

On adjusting to civilian life

“The first thing you do when you walk off the plane from coming home from a deployment is look back like, ‘Oh shit. Where’s my rifle?’ Carrying that rifle with you, or certain gear, for so long, it would be like walking away from your purse. It’s like starting all over again. It takes some getting used to. Take it day by day as it comes. Try not to allow yourself to get overwhelmed.”

On serving his country

“I get thanked a lot for my service, and I simply tell them you’re worth it. You’re worth it. And I mean that. And it’s my pleasure to serve because this country is worth it. And the people that live here, it doesn’t matter what they believe. I’m not going to get political. I don’t care. I don’t care who’s going to be president. I don’t care because I’m going to do what I’m going to do. I don’t discriminate against anybody, Republican, Democrat, Independent, I love everybody equally and I’ll fight for everybody equally.”

A Fallen Comrade

Nick Ibarra joined the U.S. Marines in 1998 and served as an active duty member until 2002. In 2005, he reenlisted in order to serve his country during the Iraq War. Here he recounts a story that happened near the end of his deployment in Iraq.

By Nick Ibarra as told to Vivian Wheeler

In the end, I did 47 convoys. Out of those, I stopped counting the number of times I got hit by roadside bombs. I stopped counting the 12th time it happened. But there was one that sticks out in my mind. I was a vehicle commander for the medic in our vehicle, and we got a communication on the radio that the bomb had gone off and there was a soldier who had been injured. The army convoy and their medic couldn’t get to the downed vehicle, so I came on the radio and said, “Hey, if you make room for us, we’ll go up there and assess the situation and help how we can.”

When we pull up, the first thing I see is the whole front quarter panel on the passenger side is just gone. You can see engine parts and things like that. And we walk around the side of the Humvee, me and the medic, and the first thing I thought is, “Why does this guy have white socks on?” because in combat boots, you’re supposed to wear black socks. And then I thought, “Why are his boots off? And why is his foot in his mouth?” And then I realized the whole bottom half of his body was gone, and it was all over the Humvee, but he was still awake. And I remember my medic looking back at me with this look that said we have to try, even if there is no point in trying.

I assisted in administrating first aid. And I remember the guy who was injured was moaning, and then he started asking about different people. And I said, “You don’t have to worry about anybody. Everybody is fine.” In the Marines, they teach you that part of the immediate action you take with somebody who is injured is you make sure they’re breathing, you stop their bleeding, start working on their injuries, and then you want to treat them for shock. So in my mind, this guy is awake so the purpose should be to keep him awake as long as possible.

So I start talking to him about his family, and we started talking about how long he had been in Iraq. And sometimes I wonder if that was a good thing for me to do because I learned that this guy, who is going to lose his life, has a wife and two kids. He was from Texas.

We got him on a helicopter and sent him on his way to the hospital. For the rest of the night on the drive, I’ve never been so scared in my life because I saw from inches away what even a small roadside bomb can do to a human being. And what’s to stop me from running over one right now, or right now. Right now. Right now.

The guy didn’t make it. Ten years went by, but I made a trip to Texas. I probably broke the law by jumping a graveyard fence on federal property, but I found his grave. It was an experience I won’t forget.

When I was going through therapy with the VA, my therapist gave me an assignment to write a letter to his family, even if I never sent it. So I found his daughter and his wife on Facebook, and I emailed them both and his daughter responded. I wrote her a letter, and it took a long time for her to respond. She thanked me for my letter. I took all of the really sad parts out of it, but I made sure she knew she was being thought of in her dad’s last moments, and that he was more worried about other people than he was about himself. We’ve kept in contact, not very often, but I see how she’s doing every once in a while.

That explosion happened in the middle of September, and it was early October when we came home. I remember that the last moment I had my feet in Iraq, we were loading an airplane, and we were on the landing strip. I remember looking out over the distance, it was night, and I remember thinking “Man, there’s a lot of people who won’t make this trip home.”