Outdoors

Beneath the Surface: Controversy on the Buffalo National River

Since C&H Hog Farms opened its operation in the Buffalo National River watershed, concerns involving the river’s safety and quality have been on the rise. We headed south to learn about the potential threats and examine the passion of the many involved.

By Savannah Waszczuk

Nov 2017

The Buffalo National River flows freely through nearly 150 of the most scenic miles in northwest Arkansas. It becomes a point of beauty for everything in its path, cutting its way through lush Ozarks forests and hugging the feet of giant limestone bluffs. The water takes on a peaceful tone as it passes over rocks and rushes through rapids, creating sounds as intoxicating as the river’s views. Together they’re a magical thing—something that’s more than enough to make you forget your worries for a while.

In 1972, President Richard Nixon designated the pristine waterway as the first national river of the United States, passing a sense of ownership along to each and every one of us. It’s our river—the residents of 417-land who frequent the area for weekend float trips and hiking adventures. It’s Arkansas’ river, often referred to as the state’s crown jewel and proven to contribute to the nearby economy. The river brought in 1,785,358 visitors and $77,556,600 in 2016 alone. It belongs to Texans and Louisianans and Missourians and Oklahomans—to all its regular guests who come to paddle downstream and camp along its rocky shoreline. But perhaps more than anyone else, it belongs to the Arkansans who live in Newton, Searcy, Marion and Baxter counties—those who have grown up with the river in their own backyards.

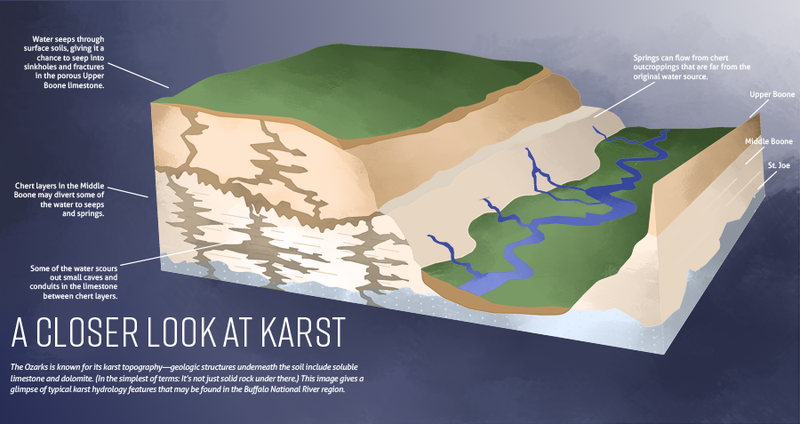

There has been an uproar about this national treasure in recent years. In 2013, C&H Hog Farms, a concentrated animal feeding operation (CAFO), began operating in the small Newton County town of Mount Judea, which is in the river’s watershed. Because water and nutrients that seep into the watershed’s groundwater might eventually make their way to the river, many fear that the farm’s waste could cause damage to the stream. C&H and the river’s watershed are also situated on karst topography—a landscape sitting atop eroded limestone riddled with fractures, fissures, sinkholes, caverns and other voids—and some say this is cause for even greater worry. Concerns continue to arise, as the river was included in American Rivers’ 2017 America’s Most Endangered Rivers list due to the possible threat of pollution. The report was accompanied by photos of an unprecedented algal bloom.

Others say there’s no reason for such concern. The American Rivers’ list was published just four months after the farm’s co-owner Jason Henson was awarded the Stanley E. Reed Leadership Award from the Arkansas Farm Bureau Federation. Arkansas Farm Bureau also recognizes Henson and the farm’s other co-owners—Henson’s cousins Philip and Richard Campbell—for their environmental concern regarding the river and the farming techniques they use to keep it sacred and safe. The farmers are known for their cooperation with the Big Creek Research and Extension Team, which was put in place by former Arkansas Gov. Mike Beebe and monitors the farm and its effects on the river and watershed. With multiple scientists and teams studying the issue, a lofty question is posed: Is the Buffalo National River really at risk?

Gordon Watkins has lived near the Buffalo National River since 1977, and he regularly recreates on the water. He leads the Buffalo River Watershed Alliance that aims to protect the river and watershed. Photo courtesy Gordon Watkins.

The People’s Passion

Newton County resident Gordon Watkins wears a weathered blue hat that reads “My Blue Heaven” in embroidered letters. This is the name of the rental cabin he owns on the Little Buffalo River, one of the Buffalo National River’s tributaries, and this cabin sits directly across the river from his home. “I’m often river-bound,” Watkins says, his salt-and-pepper speckled hair peeking out from the sides of his cap. “We have to canoe to get out sometimes. We’d canoe our kids out to the school bus at times when they were still in school.” Watkins originally moved to the area in 1977, purchasing land on which he would start an organic farm and later his rental property. “Around here, you’ve got to do alittle bit of everything to make a living,” he says.

The river and its surrounding streams have been a part of Watkins’ life for 40 years. Today, he’s the president of the Buffalo River Watershed Alliance (BRWA), a volunteer, nonprofit organization created in direct response to the approval and opening of C&H Hog Farms near Big Creek, one of the Buffalo National River’s major tributaries. “Since 2013, I’ve probably spent 20 hours a week on stuff related to this,” Watkins says, speaking to his involvement with BRWA. The nonprofit group is one of several environmental organizations that opposes the location of the hog farm, fearing that its estimated 2.5 million gallons of liquid waste per year will eventually end up contaminating the river and groundwater. Watkins says BRWA has two primary goals: to see the farm close or relocate to what many might consider a more appropriate area and to make sure that no similar facilities or CAFOs—concentrated animal feeding operations—open within the Buffalo National River watershed.

Watkins first heard of a hog farm coming into the Buffalo National River watershed in late 2012. “They had issued their permit in August 2012 very quietly with no public notice,” Watkins says. “We heard about it in December, I guess—that was the first inkling that we heard. I have full confidence that had there been a public comment period then this thing would never have been located there. There would have been too much of an outcry about it.” Typically these types of permits require more notification, Watkins says. “The county authorities are notified as well as neighboring landowners and newspapers, et cetera,” Watkins says. “But because this was the first of its kind of this type of permit that was issued, the notification requirements all fell through the cracks.”

The lack of notification is something that many individuals discuss, and they all point the wrongdoing to the state. “We lay the blame at the feet of ADEQ,” Watkins says, referring to the Arkansas Department of Environmental Quality. ADEQ could not provide comments relating to C&H because another permitting action for the facility was under review at press time. “They’re the ones who issued the permit and didn’t do their due diligence when they approved it,” Watkins says as he

discusses the state agency.

Fellow BRWA board member Ellen Corley, who has lived in Newton County since 1977, agrees. “Nowhere is the alliance against these farmers,” Corley says, referring to the local families who own and operate C&H Hog Farms. “Nowhere. And sometimes the opposition puts it that way. They’ll say, ‘Now these are good, Christian people. What are you doing? Why are you against them?’ But no. That’s not the issue. ADEQ wrongly permitted it and put it in the wrong place and allowed it to stay in the wrong place.”

Along with many others, Corley has had a longtime connection to the river. “As my children were growing up, in the summer we recreated at the Buffalo every Sunday afternoon,” she says. “My children learned to swim in the Buffalo. They were baptized at the Ponca low-water bridge.” As Corley speaks about the farm’s location, there is a hint of sadness crackling her voice. It weighs on her face. “When this issue came up, it was really just like, Why?,” Corley says. “Why would you put something like that in the watershed of a national river?”

Marti Olesen, a fellow BRWA board member and former Springfield resident who moved to Ponca, Arkansas, in 1989, agrees. “Yes, we do have a small business,” says Olesen, whose family owns a historic general store, cabins and a canoe concession along the river. “And that’s important. But to me, the most important thing is that there are so few of these rivers. Rivers this clean are so rare.” Olesen speaks of the days when she moved to Arkansas 30 years ago; her husband was one reason, and the river was the other. “To see it destroyed because of something that was misplaced in the first place, well—that would break my heart,” she says.

Steve Eddington, vice president of public relations at Arkansas Farm Bureau, often recreates at the Buffalo National River. When he’s not paddling downstream, he enjoys other adventures—this photo was taken in 2008 while he and his son, Sam, explored an area hiking trail. Photo courtesy Steve Eddington.

Farming in the Watershed

Jason Henson, farm co-owner and the “H” in C&H Hog Farms, politely declined to talk about anything involving concerns of the farm’s location for this article. “I don’t think his intent is to avoid anything,” says Steve Eddington, vice president of public relations at Arkansas Farm Bureau. “It’s just that he’s played this game before, and I don’t think he feels like he was treated fairly. As a result, he has the attitude of, ‘I’ll just let my work stand for itself, and the science that is behind it all stand for me and speak for me, and I’ll let it all stand on that.’” Eddington is referring to the public opinion that has seemingly arisen about the families who own the farm—the opinion that the farm families don’t care about the Buffalo National River.

Eddington argues this couldn’t be further from the truth. Due to his role at Arkansas Farm Bureau, he has relationships with both the Henson and Campbell families—the “C” in C&H Hog Farms—and he says they are all very much in support of the river’s safety. “Jason Henson was baptized in Big Creek,” Eddington says, his words putting his thick Southern accent on display. Big Creek is the Buffalo National River tributary situated near C&H, and it’s the main concern of many enthusiasts. “He taught his daughter to swim there,” Eddington says. “To suggest that he doesn’t have as much passion about it as person X—that’s nonsense.” Eddington himself also has a passion for the stream. “In the 40 years that I’ve lived in Arkansas, I’ve probably been to the Buffalo River 30 times,” he says.

Henson and the Campbells have had family living in the watershed for at least eight or nine generations. “It’s not like someone new just came into the area and decided to build a hog farm,” says Evan Teague, a professional engineer and vice president, commodity and regulatory affairs, at Arkansas Farm Bureau. Teague has been going to the Buffalo National River since he was a kid—he and his dad used to take their camper there for mini getaways. “Prior to Jason going into business with them, Phillip and Richard owned a hog farm,” Teague says. “They had excellent environmental records.”

After Jason and his wife, Tana, went to college and had a stint in the corporate world, they decided to move back to Mount Judea. It’s the small, familiar town where they grew up and where they graduated from high school. It’s where Jason wanted to join in the family farm business with his cousins.

“Hog farms in the Buffalo River watershed are not uncommon,” Teague says. “This is nothing new. There have been hog farms in the Buffalo River watershed since back in the ’70s, ’80s, even the ’90s.” C&H is home to 2,500 sows, which, of course, proposes the numbers argument. But this can also be seen from another point of view. “There are fewer sows associated with concentrated animal feeding operations in the Buffalo River watershed now than there were 20, 30 and 40 years ago,” Teague says.

The numbers are familiar to Teague, as there was a similar instance in the watershed some 20 years ago. “You can go back and look at the issue,” Teague says. “Go back and look at the mid-1990s. A new hog farm was proposed for the Buffalo River watershed. I think this one was proposed to be right on the Buffalo River.” The proposed farm would have been closer to the Buffalo than C&H, which is located six miles from the actual river. There was an outcry by the public in the ’90s case as well, and ADEQ initiated a study to monitor the farms and farming techniques that existed there—specifically the regulations regarding manure management. “Yes, at the time, there were some issues with those farms,” Teague says. “Those issues were not related to the location of the farms or leaking manure storage ponds, but rather manure management practices. The study resulted in changes to Arkansas’ nutrient management planning and continuing education requirements for farmers, which are still largely intact today.” Teague continues to argue that with these changes and the far better technology and farming techniques that exist today, C&H is well equipped to operate in a way that does not harm the environment, and they do so. “That’s kind of why we have stood steadfastly behind C&H,” Teague says. Since the farm’s initial permit application, the state has changed the public comment notification requirement for the general CAFO permit. “They did everything they were told they had to do,” Teague says of the farmers. “From a right-to-farm perspective—that’s kind of where we’re coming at this from—they did everything anybody asked them to do. What else can you expect a landowner or a farmer to do?”

The Concerns About Karst

Ask anyone who opposes the farm’s location their reason for doing so, and the area’s karst topography will be one of the first things they mention. Karst refers to the landscape containing limestone that has been partially eroded—it’s been compared to the makeup of Swiss cheese. “There are a lot of assumptions with water quality monitoring that go out the window when you’re in karst environments,” says Jessie Green, executive director and waterkeeper for White River Waterkeeper.

Green formerly worked as a senior ecologist for ADEQ, but she left the state organization to start this nonprofit organization, which is a part of Waterkeeper Alliance. She’s well-versed on water quality, reciting facts and figures as quickly and confidently as most people recite the alphabet. Green and many others argue that if C&H were located on a typical landscape in a watershed near a river, there would be sufficient data to look back on and use for determinations. Protecting the river through these evaluations could be more scientifically accurate. But karst makes this much more of a challenge, they say. “You have to visualize two layers,” says Caven Clark, who works for the National Park Service. “One is the surface watershed, and one is the karst watershed. Both are equally important, and both are equally susceptible to the factors which compromise their quality.”

Carol Bitting, a Newton County resident who has lived on the Little Buffalo River for more than 15 years, is also very familiar with the area’s karst landscape. She knows the river inside and out—she’s floated it, backpacked along it and even swam most of it over and over throughout the years. And she’s also explored the area around it. “Me and my husband met because we’re both cavers,” says Bitting. Bitting’s husband, Chuck, works for the National Park Service, and one of his duties there is acting as a cave specialist. Carol has volunteered to explore many of the caves in the watershed with him. “Traveling through caves and being a caver—you see how that water flows,” Bitting says. “A good example of this is to go to Top of the Rock and sit there and look at what can happen.” Bitting is referring to the sinkhole that collapsed at Top of the Rock in 2015.

Carol Bitting, a Newton County resident who has lived on the Little Buffalo River for more than 15 years, is also very familiar with the area’s karst landscape. She knows the river inside and out—she’s floated it, backpacked along it and even swam most of it over and over throughout the years. And she’s also explored the area around it. “Me and my husband met because we’re both cavers,” says Bitting. Bitting’s husband, Chuck, works for the National Park Service, and one of his duties there is acting as a cave specialist. Carol has volunteered to explore many of the caves in the watershed with him. “Traveling through caves and being a caver—you see how that water flows,” Bitting says. “A good example of this is to go to Top of the Rock and sit there and look at what can happen.” Bitting is referring to the sinkhole that collapsed at Top of the Rock in 2015.

In an attempt to figure out how water moves in this karst landscape area, John Van Brahana, who holds a Ph.D. in hydrogeology, formed the Karst Hydrogeology of the Buffalo National River (KHBNR) team, which is now sponsored by the Patagonia Foundation. KHBNR performed a large dye tracing study to learn where the water flows, and Bitting and other volunteers spent hundreds of hours helping out. Teresa Turk, a scientist who brings decades of experience with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to the KHBNR team, says the findings were huge. “The dye from the injection site, which was in really close proximity to where manure was being spread—it traveled almost over two miles in less than a week underneath a fairly large ridge—what we would almost call a mountain in the Ozarks,” Turk says. Turk moved back to northwest Arkansas five years ago to be near the Buffalo River, but her earliest memory there is exploring fish through child-sized goggles at age 10. Today, she fears for the safety of those fish and the Buffalo National River as a whole. “The overall implication of this study is that the hydrology out there is really complex,” Turk says. “The dispersal of nutrients is wide, broad and has far-reaching implications to the whole area. Manure is not being constrained to just that area. It’s going wide and far. When you spread almost 3 million gallons of hog manure every year, it’s gotta go somewhere.”

Others, including the team at Arkansas Farm Bureau, note that they are also aware of the concerns that come with karst topography. “The opposition has alleged that Farm Bureau and the others have failed to acknowledge the presence of karst, which is not true,” Teague says. “We realize there’s karst in that part of the state. There always has been. And guess what? There has also always been animal agriculture in that part of the state, whether it’s poultry, whether it’s hogs, whether it’s cattle—and you don’t see a variation. We’re not aware of any major impacts of subsurface groundwater as a result of animal agriculture in that part of the state.”

Part of the reason karst doesn’t affect the watershed, Teague argues, is because of the depth of the soil. “What they also fail to tell you is that there’s three to four feet of topsoil, particularly in the areas around Big Creek,” Teague says. He goes on to speak about the dye-tracing studies, but states that an old 40-foot hand-dug well was used as an injection point. This is not representative of how the farm operates, Teague argues, as the manure is applied to pastures in small, regulated amounts.

Andrew Sharpley, who holds a Ph.D. in soil science and works for the Division of Agriculture in the Crop, Soil and Environmental Sciences Department at the University of Arkansas, was selected to lead the Big Creek Research and Extension Team (BCRET) that was put in place by former Arkansas Gov. Mike Beebe. The study started in fall 2013 in an effort to provide scientifically rigorous information on any potential impacts of the farm on Big Creek, including levels of bacteria and nutrients such as phosphorus and nitrogen, and it has published quarterly reports since that time. When Sharpley speaks about the karst, he understands the concern and says it is something they’re cautious of. “We know there’s karst, and we know there are sinkholes,” Sharpley says. “There’s a buffer around those [where] they can’t apply manure. There’s geology mapping that gives a pretty good idea where sinkholes—especially those that come to the surface—are, and those are obvious and mapped on a farm plan. There’s a 100-foot buffer around them, and they’re required not to apply there.”

A Closer Look at the Farm

C&H Hog Farms is a privately owned farm that originally contracted with Cargill, a large, privately held corporation involved in trading, purchasing and distributing grain and other agricultural commodities. In July 2015, JBS USA Pork entered an agreement with Cargill to acquire the company’s U.S.-based pork business, and this included C&H Hog Farms. C&H’s current contract is with JBS, and JBS supplies the hogs. Cheri Schneider, who works in communications for JBS USA, sent the following statement: “C&H Farm is an independent, locally-owned and operated family farm that raises hogs under contract for JBS USA,” it said. “We do not control or own the farm; however, it is our understanding that C&H is fully compliant with all applicable regulations and standards and continues to make significant investments to ensure environmental compliance.”

C&H is a farrow-to-wean operation. It is home to 2,500 sows, and those sows give birth to piglets. The piglets are raised to a size of about 12 to 15 pounds, and then they are shipped to other states. They are finished and slaughtered in surrounding states including Texas, Iowa, Kansas and Missouri, and the meat is sold across the U.S. and possibly overseas. But it’s not the farming process that BRWA board members and others are concerned about; it’s what happens to the waste from these sows and piglets.

“There’s a line that goes around that says hogs produce as much waste as six or eight people do,” Watkins says, speaking on behalf of the BRWA. “And that’s a fact. They produce copious amounts of feces and urine. So this operation with 2,500 sows produces more waste than the city of Harrison—a city of 12,000 people.” Watkins goes on to explain that 12,000 is a conservative number, and some people quote the waste from C&H to be equivalent to something closer to 20,000 to 30,000 humans. “Well, the city of Harrison has a waste-water treatment plant,” Watkins says. “You know, it goes through this elaborate system to purify it before it’s disposed of, ultimately. This CAFO does not do anything like that. They store it in a pond, then they spray the raw waste on the fields. Can you imagine the city of Harrison doing that?”

John Bailey, director of environmental and regulatory affairs with Arkansas Farm Bureau, explains the other side of this argument. “Essentially, what you have is oversized lagoons with 18-inch compacted clay liners, sitting on top of a clay outcropping, much of what can be used as a clay liner itself,” says Bailey, who is from Springdale, Arkansas, and floats the Buffalo National River annually. These ponds being oversized, as well as the lining that has formed, are considered measurements of safety against seepage and leakage. The liquid waste from the farm is stored in these holding ponds until it is spread on some 35 fields permitted to be used by the farm. “But the real science behind this application are the soils,” says Bailey, who is also a professional engineer. “Soils do all the work to purify the water. Sure, if you just want to talk about karst and take the soils away, yes, that’s a problem. But the soils are there, and they do their job.” Sharpley from BCRET agrees. “That soil acts as a natural buffer for cleansing the water that moves through it,” he says. “The soil varies in thickness. Any rainfall, sludge, slurry, manure—it has got to go through several feet of soil before it gets to what we might think of as karst rock layers.”

Many of these spraying fields are owned by other area farmers, and many are planted with Bermuda grass and fescue, which Teague says were approved in the farm’s nutrient management plan due to their absorption rates of the nutrients that can become oversaturated—particularly the phosphorus and nitrates that could threaten water quality. Teague also argues that C&H’s application rates are more than conservative. “If you take that two and a half million gallons [of waste] and just assume that you would apply all 2.5 million gallons over their available land application acreage, it would be less than one-eighth of an inch,” Teague says. “And they don’t apply it all at one time, or all at the same time.” Also due to the nutrient management plan and with their permit, C&H can apply at either low or medium rates (risk categories include low, medium,high and very high). “ADEQ set the limit to say you cannot apply at high or very high rates,” Bailey says. “Every application is at low. [Henson’s] phosphorus index has to spit out a low risk in order for him to apply. It’s not medium—it’s low. And that’s his choice.”

Bailey goes on to state C&H might even be a benefit to the watershed. “Everyone perceives that there will be an increase in the amount of nutrients to the Buffalo River,” Bailey says. What people don’t realize, Bailey says, is that C&H Hog Farms is permitted to apply waste on fields and pastures, and these fields and pastures were long in existence prior to C&H ever being in operation. Since these fields already existed and were being farmed, they were receiving fertilizer application, whether through chicken litter or commercial fertilizer products. “I’d like to point out that they don’t need a permit to do that,” Bailey says. “So, if they could get a truckload of chicken litter, they’d put it out. With C&H, they have only a permitted amount they can put out, so it’s 100 percent managed. In reality, nutrients could actually be reduced in the watershed as a result of C&H being in operation.” A decrease in nutrients would be considered good.

Wading through Murky Waters

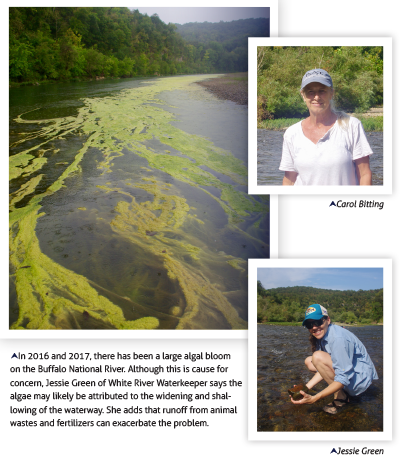

When it comes to worries of the watershed, the location of C&H is not the only cause for concern, and people who fall on both sides of the issue will tell you that. “I assume that we have a lot of issues with failing septic tanks throughout the watershed,” White River Waterkeeper’s Green says. “We also have high E. coli.” There is an additional concern regarding feral hogs and algae. “There was a really large algal bloom in 2016, and there was another in 2017,” says Turk from KHBNR. Some say the blooms might be related to waste from the farm, but others, including Turk, say there’s no way to prove that at this time. “This river is in trouble, and not just from the hog farm,” Turk says.

One thing that gives some individuals hope is the talk of microbial source tracking. This is a set of techniques used to determine the source offecal indicator bacteria. “Microbial source tracking will help us figure out our sources, but also help us figure out what our next steps need to be,” Green says. She hopes to start the tracking through her role as White River waterkeeper one day in the future, and she plans to start collecting samples for it next spring. A slight problem with it, however, is that even if the tracking determines pollution from a specific source, such as hogs, it might be from feral hogs, or it might be from C&H hogs, or it might be from any other hogs located and farmed within the river’s watershed.

As more time passes, there will also be more conclusive data available from BCRET’s study—it was planned to be a five-year study from the start. The quarterly reports available today can all be viewed online, but even these findings are interpreted in a variety of ways. “At the moment, we haven’t seen any dramatic changes, trends or shifts,” says Sharpley, who also specifically stated BCRET does not claim to be on a particular side of the issue. He says it takes time to come to reliable conclusions for various reasons. “We want to make sure that, over the long term, the ability for the soil to buffer those nutrients isn’t compromised,” Sharpley says. One thing that’s for sure, though, is that the watershed is under close watch, and particularly in the Big Creek area. “It’s being looked at more intensely then probably anywhere else in the country,” Sharpley says.

The farm’s cooperation helps. “Jason himself has said—and that’s why he agreed to subject himself to such a rigorous study through the BCRETprocess—he said, ‘If I’m impacting this area and this watershed, I want to know before anybody else so I can fix the problem,’” Teague says. “And that’s why he agreed to do the study and involve BCRET, because he wanted to know himself. He said, ‘If I find that something I’m doing is not working the way it should, I’ll change it.’”

Whether Henson will ever need to change anything is yet to be determined. One thing that’s obvious, though, is that each and every person involved has a passion for the Buffalo National River and its watershed. The very place where Jason Henson himself was baptized and where 417-landers go for weekend float trips. Where Ellen Corley took her kids each Sunday and where Teresa Turk first fell in love with aquatic life. Where Arkansas Farm Bureau employees go on annual float trips. “Farm Bureau has many staff and many members that enjoy recreation and outdoors,” Teague says, explaining the organization’s passion for the Buffalo National River, as well as their strong support of the right-to-farm law. “I think—the whole point to all of this is—we believe that it can all coexist.”

Watershed Watch

The Buffalo National River watershed, and particularly the Big Creek tributary near C&H Hog Farms, is arguably one of the most studied watersheds in the country. These are some of the teams collecting data for various studies.

Big Creek Research and Extension Team (BCRET)

BCRET was put in place by former Arkansas Gov. Mike Beebe and includes scientists from the University of Arkansas’s Division of Agriculture. Learn more about the project and its team

members online at bigcreekresearch.org and read quarterly project reports dating to as early as October–December 2013.

National Park Service

The National Park Service has been collecting data up and down the Buffalo National River since 1985. It continues to collect samples. Find more information and see various reports online at nps.gov/buff.

Karst Hydrogeology of the Buffalo National River (KHBNR)

KHBNR is an independent research project that was initially designed and directed by eminent karst hydrogeologist John Van Brahana. Its purpose is to assess and document water quality of surface water and groundwater as it flows through the watershed’s karst landscape. Learn more about KHBNR at buffaloriveralliance.org/KHBNR.

US Geological Survey (USGS)

The USGS monitors water quality throughout the state of Arkansas, including multiple spots along the Buffalo National River and its tributaries. More information and readings can be found online at waterdata.usgs.gov/ar/nwis.

Arkansas Department of Environmental Quality (ADEQ)

While the National Park Service does its own testing, it also partners with ADEQ to assist in its testing. (Water quality sites are collected by Buffalo National River staff using ADEQ methods and are passed to the ADEQ Laboratory.) The state also does additional monitoring. You can find more information online at adeq.state.ar.us.